7th Grade Westward Migration Inquiry

Was It Destiny to Move West?

Download Entire Inquiry Here

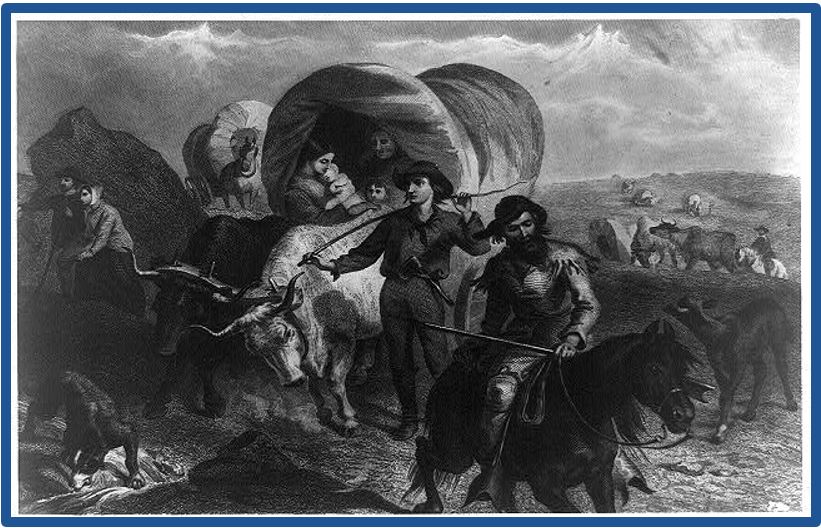

Felix Octavius Carr Darley (artist) and Henry Bryan Hall (engraver), engraving of people moving west, Emigrants Crossing the Plain, 1869. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-730. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93506240/.

Download Entire Inquiry Here

Felix Octavius Carr Darley (artist) and Henry Bryan Hall (engraver), engraving of people moving west, Emigrants Crossing the Plain, 1869. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-730. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93506240/.

Supporting Question 1- What factors influenced westward expansion?

- Source A: Unknown author, protest song sung by mill workers, Lowell, Massachusetts, 1836

1836 Lyrics Sung by Protesting Workers at Lowell

Oh! Isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I,

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh! I cannot be a slave, I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty,

That I cannot be a slave.

Harriet Hanson Robinson, Loom and Spindle or Life among the Early Mill Girls. New York: T. Y. Crowell, 1898: 83–86. Public domain. Available at the History Matters website: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5714/.

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh! I cannot be a slave, I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty,

That I cannot be a slave.

Harriet Hanson Robinson, Loom and Spindle or Life among the Early Mill Girls. New York: T. Y. Crowell, 1898: 83–86. Public domain. Available at the History Matters website: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5714/.

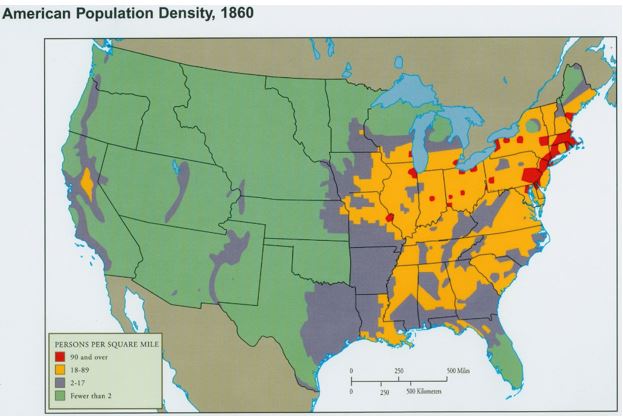

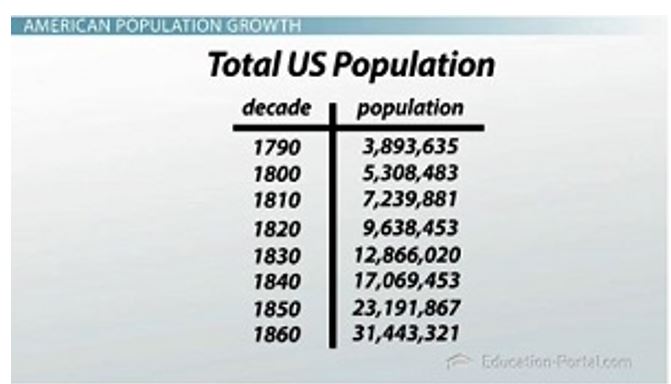

- Source B: Image bank: Maps and table showing 19th-century population and population density

Image 1: United States Population Density, 1820.

Courtesy of Dr. Gayle Olson-Raymer, Humboldt State University

Courtesy of Dr. Gayle Olson-Raymer, Humboldt State University

Image 2: United States Population Density, 1860.

Courtesy of Dr. Gayle Olson-Raymer, Humboldt State University.

Image 3: Total United States Population 1790–1860.

The Study.com. Used with permission. http://study.com/cimages/multimages/16/population-chart.jpg.

Courtesy of Dr. Gayle Olson-Raymer, Humboldt State University.

Image 3: Total United States Population 1790–1860.

The Study.com. Used with permission. http://study.com/cimages/multimages/16/population-chart.jpg.

- Source C: Excerpts from "The Great Nation of Futurity"

- Source D: Map of United States territorial acquisitions from 1783 to the present, no date

Territorial acquisitions of the United States from 1783 to the present.

Created by US Department of the Interior & US Geological Survey. Public domain.

Created by US Department of the Interior & US Geological Survey. Public domain.

- Source E: James K. Polk, speech that announced the discovery of gold in California, “Fourth Annual Message” (excerpts), December 5, 1848 Public domain.

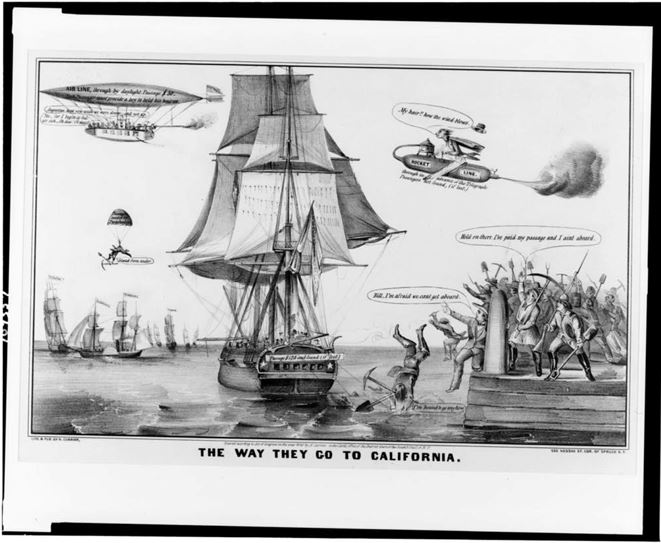

- Source F: Image bank: The California gold rush

Image 1: Artist unknown, advertisement for traveling to California by clipper ship, c1840s.

Clipper ship advertisement, engraving by G.F. Nesbitt & Co., printer. Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library. http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf1r29p10v/?layout=metadata.

Image 2: N. Currier, lithograph about the Gold Rush, The Way They Go to California, 1849.

“The Way They Go to California,” lithograph by N. Currier. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-05072. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/91481165/

Image 2: N. Currier, lithograph about the Gold Rush, The Way They Go to California, 1849.

“The Way They Go to California,” lithograph by N. Currier. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-05072. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/91481165/

- Source G: Excerpt from the Homestead Act of 1862

Supporting Question 2- What new technologies influenced westward expansion?

- Source A: Image bank: Maps of the Erie Canal routes

Image 1: Map of the Erie Canal routes.

Public Domain. New York State Archives. http://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/Occurrence/Show/occurrence_id/1827

Public Domain. New York State Archives. http://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/Occurrence/Show/occurrence_id/1827

Image 2: Map showing 19th-century canals and canals still operating today on the Erie Canal system.

© Erie Canalway, National Heritage Corridor.

- Source B: Chart comparing travel by dirt road and travel by the Erie canal, “Travel During the Erie Canal Era,” circa 1825

Created for the New York State K–12 Social Studies Toolkit by Binghamton University, 2015 based on data from “Erie Canal Freight” in Erie Canal: New York’s Gift to the Nation. F. Daniel Larkin, Julie C. Daniels and Jean West, ed .Albany, NY: New York State Archives Partnership Trust, 2001

- Source C: Paul Volpe, master’s thesis project on the influence of the Erie Canal, Digging Clinton’s Ditch: The Impact of the Erie Canal on America, 1807-1860 (excerpt), 1984 Reprinted with permission from the American Studies Programs at the University of Virginia, author Paul Volpe, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma02/volpe/canal/firstpage.html.

- Source D: Image bank: Technologies of the mid-19th century

Image 1: William Strickland, engraving showing steam a steam locomotive and railway cars, Rear and Side View of George Stephenson’s Steam Locomotive and Railroad Cars of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, 1826.

Engraving from William Strickland, Reports on Canals, Railways, Roads, and Other Subjects, made to "The Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Internal Improvement." Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea, 1826. Public domain. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-110386 http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2006675893/

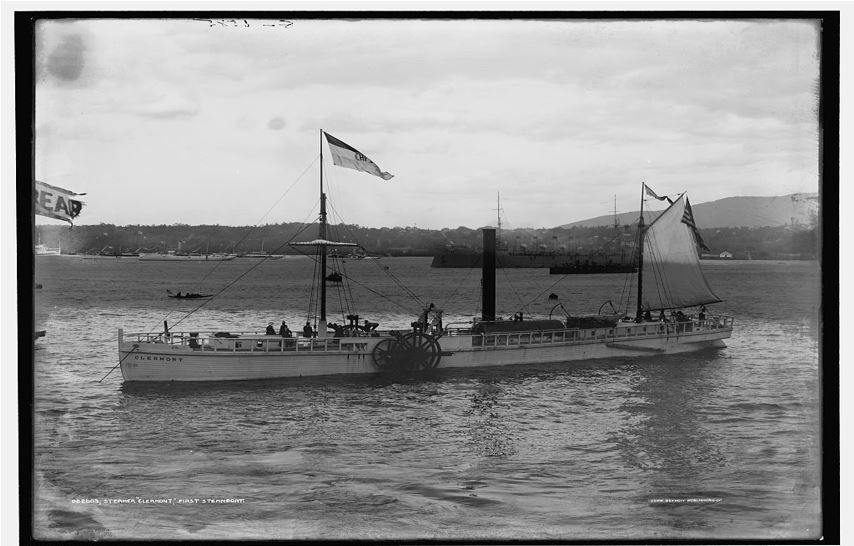

Image 2: Photographer unknown, photograph of a steamship, Robert Fulton’s Clermont, the First Steamboat, on the Hudson, c1909. NOTE: This photograph is likely of a replica of the Clermont.

Courtesy of the I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-det-4a16095. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/det1994012454/PP/.

Image 2: Photographer unknown, photograph of a steamship, Robert Fulton’s Clermont, the First Steamboat, on the Hudson, c1909. NOTE: This photograph is likely of a replica of the Clermont.

Courtesy of the I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-det-4a16095. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/det1994012454/PP/.

Image 3: Felix Octavius Carr Darley (artist) and Henry Bryan Hall (engraver), engraving of people moving west, Emigrants Crossing the Plains, 1869.

Felix Octavius Carr Darley, Emigrants Crossing the Plains, engraving by Henry Bryan Hall, Jr. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1869. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-730. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93506240/.

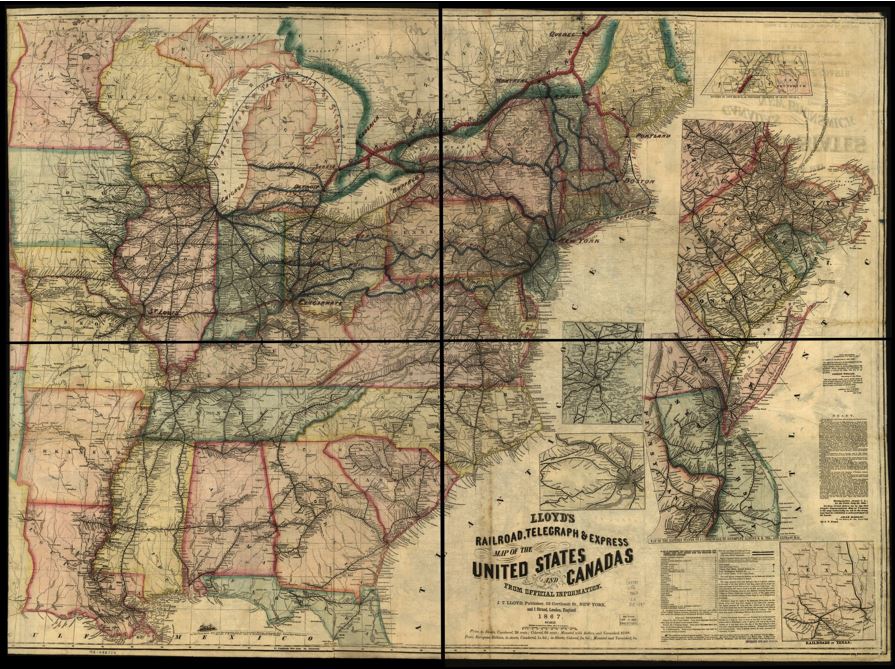

Image 4.James Lloyd, map of travel and communication lines, Lloyd’s Railroad, Telegraph, and Express Map of the United States, 1867.

Lloyd's railroad, telegraph & express map of the United States and Canada from official information. Public domain.

Library of Congress: 98688334. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/98688334/.

Felix Octavius Carr Darley, Emigrants Crossing the Plains, engraving by Henry Bryan Hall, Jr. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1869. Public domain. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-730. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93506240/.

Image 4.James Lloyd, map of travel and communication lines, Lloyd’s Railroad, Telegraph, and Express Map of the United States, 1867.

Lloyd's railroad, telegraph & express map of the United States and Canada from official information. Public domain.

Library of Congress: 98688334. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/98688334/.

- Source E: Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright, maps of changing rates of travel in the United States, 1800–1857, Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, 1932

Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright, Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States, (pages 138a, b, c, and d). Carnegie Institution for Science: Washington, DC, 1932. Used with permission.

Supporting Question 3- What conflicts arose from westward expansion?

- Source A: Timeline of European and United States conflicts with Native Americans, 1715–1842, 2015

- 1715–1717: The Yamasee War was a series of violent conflicts between American colonists and a Native American confederation centered in South Carolina. The conflicts led to disruption of many Native American alliances and migration and loss of land for several groups, including the Yamasee and Apalachicola.

1754–1763: The French and Indian War was a conflict between the British and French in North America that involved Native Americans in the Haudenosaunee Confederation. The Haudenosaunee sided with the victorious British in the conflict. While the defeat of the French allowed Native Americans and the Haudenosaunee to consolidate their power, it also created new hostilities with the British over settlement and land borders.

1763–1766: Pontiac's War was an unsuccessful effort led by Ottawa leader Pontiac and a loose confederation of Native American groups to drive British soldiers and settlers out of the Ohio River Valley after the French and Indian War. The “Devil’s Hole Massacre” of 72 British soldiers on a supply train by Senecas, Ojibwas and Ottawas near Fort Niagara was one notable success. The conflict is often remembered for the smallpox-infested blankets British officers gave to Native Americans at Fort Pitt in hopes that the disease would spread and decimate the Native American populations.

1811–1813: Tecumseh’s War was a conflict between the United States and a Native American confederacy led by Shawnee chief Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa (known as “The Prophet) in the Northwest Territory. American troops led by future president William Henry Harrison attacked and destroyed the native settlement at Prophetstown in what is known as the Battle of Tippecanoe. As a result, the confederation led by Tecumseh allied with the British and Canada during the War of 1812.

1813–1814: The Creek War, also known as the Red Stick War, was a conflict among different factions of the Creek Nation and US and European powers. Led by future president Andrew Jackson, US troops defeated a faction of Creek warriors, which led to the disputed August 8, 1814, Treaty of Fort Jackson, where the Creek Nation ceded 21,086,793 acres in Georgia and Alabama.

1817–1818: The First Seminole War began after General Andrew Jackson led troops into then Spanish-owned Florida in an attempt to recapture runaway slaves. Jackson and his troops burned and seized towns along the way. The war was instrumental in Spain’s decision to cede Florida to the United States in 1819.

1832: The Black Hawk War occurred in northern Illinois and southwestern Wisconsin. The Sauk and Fox tribes were led by Chief Black Hawk in an attempt to retake their homeland. Native American groups in the area lost millions of acres of land as a result.

1835–1842: In the Second Seminole War, the Seminoles under Chief Osceola resumed fighting for their land in Florida. Over many years, the Seminoles defended their territory but were ultimately defeated and lost most of their land. While most Seminoles were forced to move west to Indian Territory, a small number remained in Florida, where their ancestors still live today.

Created for the New York State K–12 Social Studies Toolkit by Binghamton University, 2015

- 1715–1717: The Yamasee War was a series of violent conflicts between American colonists and a Native American confederation centered in South Carolina. The conflicts led to disruption of many Native American alliances and migration and loss of land for several groups, including the Yamasee and Apalachicola.

- Source B: Map of military activities during the Mexican-American War, 1846–1848, 2012

Created by Kaldor, 2012. Reprinted under Creative CommonsAttribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mexican%E2%80%93American_War_(without_Scott%27s_Campaign)-en.svg